|

There are seven things you control that directly influence your Service bottom line.

1 Calendar Utilization 2 Daily Clock Hours 3 Number of Technicians 4 Proficiency 5 Effective Labor Rate 6 Gross Retention Rate 7 Expenses This installment deals with Effective Labor Rate. Why is it important? As I mentioned earlier, the only thing a service oriented organization has to sell is time. Everything else follows that. You buy it from an employee and sell it to a customer. You need to know how much you are collecting per hour. At this time of year store owners are often faced with decisions about pricing and compensation. You are trying to decide if you should raise your prices or if you can afford to pay the technicians more. Until, and unless, you know how much an hour you are actually collecting, you cannot determine either. Let’s say you post your labor rate where everyone can see it (In some states you must). Let’s say it is $120. It’s a lie and you know it. You can’t avoid it. It is a lie because you seldom collect that amount. Competitive items get priced down to match or beat the competition. Some jobs get discounted so you can capture the work. Many services you do for free to create or maintain loyalty. Technicians sometimes take far longer than you expected when you quoted the price (Some states require that you stick to your quote within a certain range). It also depends heavily on your work mix and the type of work you do! There are so many reasons you don’t collect your posted rate. Customers look at your posted rate and assume anything you do is going to cost them $2 a minute. They know they don’t make that much and are hesitant to even talk to you about things they might like above and beyond their primary need. To make things worse your technicians look at the posted rate and wonder why they may only be getting paid $24 for every one of those hours. If you are really keeping 80% of every dollar you collect you are probably too busy spending your money to be reading this post. We’ll look at this more closely when examining “Gross Retention Rate”. You can have a low effective labor rate and be having one of the best months you have ever had. Let me explain. Let’s say you do a promotion of a simple maintenance item that is steeply discounted and brings a flood of new traffic to your store. It fills your shop. Many up-sells and a few unit sales are made. You add several first time customers to your client list. The high volume of discounted items makes it look like you are doing a bad job even though you rock!!! Who wouldn’t want a shop full of work over and empty one with a high effective rate! It would be great to have both. So, how do you accurately assess your effective labor rate? You could just divide whatever you collect by the number of hours you were open. What if it is low? There are so many reasons why it might be low and too little information to diagnose why. Remember this is a LABOR rate. When thinking of profit, it refers to how much you sell each billable hour of labor you purchase. Using the Numbers Worksheet, the forecast breaks out the number of hours you were open, the number of hours the technicians were working on jobs and the number of hours you were able to bill customers. It divides the labor sales by the billable hours for each technician and for the entire shop. You can use it to run different scenarios and see the impact on your bottom line. i.e. Add the cost of a promotion for a simple, repetitive maintenance item. Bump up the tech efficiency based on how quickly they can do it compared to a more difficult repair. Increase the gross retention rate based on the fact that lower paid technicians will be doing these jobs. There are other things to consider when doing a promotion, but this will tell you if you will make more or less money doing it. How do you increase your effective labor rate? If your prices are not obviously lower than your competition and market, just raising them isn’t an option unless you provide service that is noticeably different and valuable enough to charge a premium for. You may be able to increase it in several other ways.

Next: Controllable #6 - Gross Retention Rate.

0 Comments

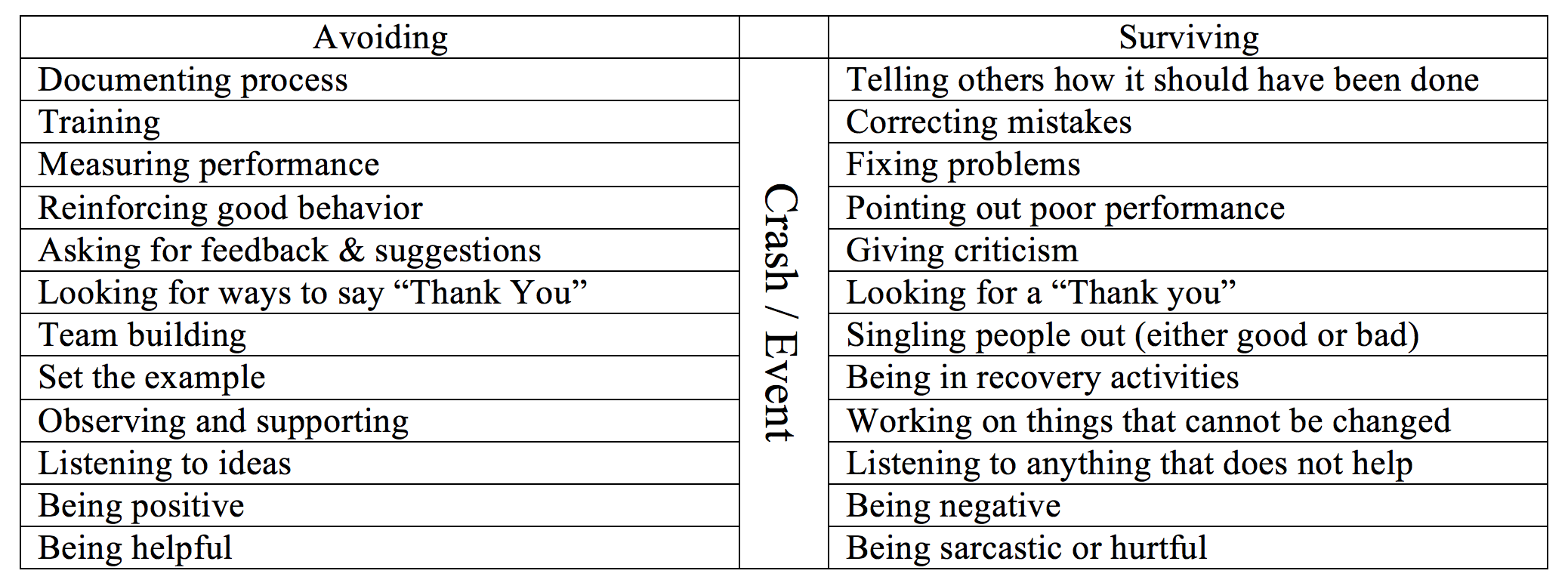

Boarding a Plane I was in the Nashville airport recently traveling home from a dealer visit. The dealership I was at is very good and continually getting better. An issue I have been helping them with is getting ahead of issues. When there is an issue they are experts at making things right. Few are better at making an unhappy customer happy again. Research tells us that customers who had an issue resolved to their satisfaction are more loyal than customers who never had an issue in the first place. The problem is, it extracts a huge toll on time and resources. Plus, we never know how many customers were unhappy and never let us know. The related tension creates a culture focused on issues rather than successes and can be tough on employees. Being in the airport reminded me of a recent article I read in Automotive News about how differently the auto industry and the airline industry think about safety. The auto industry has focused on crash survival for a century and have done an amazing job. Automobiles are vastly safer than they have ever been. Even though there are more accidents, significantly fewer people are injured or killed than ever. This is very good but consider this. Nearly all the technology, time and money is focused on what happens after the crash. There is a direct correlation to a typical managers’ day inside most dealerships. When thinking of safety, the airline industry begins from a completely different starting point and mindset. Since no one normally survives an extreme and rapid loss of altitude or survives a 500-mph sudden stop, they spend the clear majority of their time and resources focused on crash avoidance. Because they think differently, they behave differently. So, what? Well, look at the difference between avoiding and surviving as it applies to my friends’ dealership. I think one of the clear differences is that when there is a crash at the dealership no one dies. In fact, no one may even know. The customer just goes away and we never hear from them again unless they are upset enough to take some of their time to post something nasty on the internet. Same with employees, they seldom fall over after being injured by a manager. They just decide to quietly look for another job and eventually leave. Crash Avoidance: The airline industry usually gets its pilots from the military. These are mostly young people who have dreamed of being a pilot, gone to college and spent thousands of hours conditioning their bodies and minds. They have been relentlessly tested and earn higher rank as they prove their proficiency. They don’t sit in the pilot seat until they prove themselves. Even then, they are with an instructor. Crash Survival: Managers are experts at apologizing, redoing and placating customers. Why? They are the only ones with the skill or authority. Nearly no-one grows up hoping to be a service advisor or car salesperson. We hire people with little or no training and put them in front of customers within a week of their arrival. They learn their trade on your customers with no skill path or internal certification. Because of this, front-line folks are seldom equipped or have the authority and budget to do whatever it takes to make a customer happy. Crash Avoidance: Whether a pilot, flight attendant or ground crew they use tools like the pre-flight checklist to ensure everything goes right. They don’t leave things to chance. They document it. They measure it. They drill constantly. They don’t vary from or change the established process. Everyone knows what it is and everyone can see if it is being followed. Crash Survival: Managers are experts at discovering what went wrong and pointing it out. Why? They are the only ones that know what should have happened. The processes are generally tribal folklore, stories passed down from one generation to the next. If the process is documented, few can find it or recite it. Process checklists and consistent process training are often non-existent. Process is used to assign blame for not following it in the wake of an issue. Crash Avoidance: The airline pilots, flight attendants, gate agents, ground crew relentlessly practice. They use simulators and learn how to handle even the rarest situations they may face before they must. They don’t wait to practice until a plane hits a flock of geese on takeoff over one of the most heavily populated places on earth. They are prepared and confident. Crash Survival: Managers are experts at “keeping people on their toes”. Why? They make sure their people are aware of their mistakes. They put employees in situations they have never dealt with before using equipment they are not familiar with and let them practice on their customers. Then they wait for the crash. When things go wrong the focus is on what their people did wrong instead of what their manager should have done. It is too late to reinforce the things employees do right. We teach them to prepare for the crash, not how to avoid it. Crash Avoidance: Everyone knows each other’s job and are empowered to say something. They work together. If anything goes wrong everyone is affected. Studies show that airlines with the highest incident rates are the ones where it is unacceptable for a subordinate to question a superior. Crash Survival: Managers are experts at taking control and looking like heroes. This is a huge red flag! The very fact that there is a situation points to the fact that they didn’t avoid it. To avoid a crash, you need to value everyone in the organization, their opinions and talents. Create a culture where people speaking up is welcome. You see, in a dealership no one dies. In a plane, everyone does. Start by tracking how many issues arise. The goal is to reduce the number. If you are not good at that you shouldn’t be asking to fly the plane! I was with a pilot who told me that none of the items on a preflight checklist were put there just because someone thought it was a good idea. They are there because something bad happened that we don’t want to happen again. He said, “Good judgement is the result of experience. Experience is the result of bad judgement”. An incident that results in no change in your routine is a sure sign that it will happen again. Look at how you and your leadership are using your time. Create a chart with two columns and track what you are doing every half hour for a month. You will begin to get a very clear picture. Here is the thing to remember as a store owner. You are paying for their time! How it is being used is the most important thing! Are your managers spending their time prior to or after events happen? Consider time spent preventing issues as extremely valuable. Consider time spent after the issue as worthless other than to clean up the carnage and settle the law suites. How good is your organization at avoiding crashes? You could point to your online reputation, customer satisfaction index or policy account, but I have a better idea. Far more of your customers arrive at your store for service than sales. Tomorrow, drive up to your service entrance. Shut off the engine. Close your eyes and take a deep breath. Imagine you are going on vacation with your family. Ask yourself, “If this place were an airport and the people inside were ground crew and pilots, would I board the plane”. There are seven things you control that directly influence your Service bottom line.

1 Calendar Utilization 2 Daily Clock Hours 3 Number of Technicians 4 Proficiency 5 Effective Labor Rate 6 Gross Retention Rate 7 Expenses This installment deals with Proficiency. Why is it important? You have begun to measure “Utilization” of time. You have decided how many days you will be open, how many hours you will be open each day and how many technicians you will employ. If you have ever built a race engine, this is similar. There was a lot of anticipation. You took every detail into consideration, matched up the best available parts that compliment each other and learned the best techniques to put them all together. At some point you needed to move past the anticipation, start the engine and see how much horsepower it produced. Many an engine builder has been surprised (negatively or positively) at the output of their project. When Ron Stoner and Skip Vandervall wrote “The Seven Controllables of Service Department Profitability” they called this measurement “Productivity”. When I was a service manager it was the primary measure I was most interested in. In its simplest form it is the billable hours produced as a percent of clock hours available. i.e. 10 techs - 8 hour day - 100 hours billed - equals 125% productivity. What do you do if the productivity is low? You quickly learn that there are actually two very important elements that make up productivity. Thus, the heated discussions that always come up whenever it is mentioned. People are talking about three different things. Folks can’t even agree on what to call them. Some people came up with “Proficiency” as a way to explain the combination of the two key elements. Ron & Skip had it wrong. There are 8 controllables. They talked about, but left out technician efficiency. I have changed the forecast tool to utilize it. Let me explain. You will remember I drew an analogy between a combustion engine and a service shop. The combustion engine draws in air, mixes it with fuel. lights it up and converts the heat to motion. A service shop engine opens the doors, adds some techs, gives them what they need and converts time into money. Once a technician arrives, any time not spent working on a job is lost. You cannot recover it. I see this in shops where techs come in late because they have gotten used to advisors not having jobs ready to hand out when they arrive on time. It is especially evident in Marine where large amounts of time can be lost moving boats to and from the water or storage. I also see it at parts counters where nothing starts until a tech requests a part and discussions of weekend activities begin to add up into mountains of non-refundable hours. How effective an organization is at keeping technicians productive needs to be measured. It is the first important element and is what I now refer to when using the term, “Productivity”. In its simplest form it is the hours spent working on jobs as a percent of clock hours available to work on jobs. The second and missing element is technician “Efficiency” or how fast they complete jobs. In its simplest form it is the hours billed as a percent of hours spent working on jobs. So, what would high productivity look like? A technician arrives and has a job in their bay. He punches in the time clock, punches on that job and starts working. He doesn’t need to stop to obtain parts or find tools. When he is done there is another job waiting. What is efficiency? Once on a job he works smart and completes it quickly and accurately the first time. Previously, in the forecasting tool we would multiply the total clock hours available by “Proficiency” to determine how many billable hours the shop will produce. In the new version we multiply the total clock hours available by “Productivity” to determine how many of those hours the techs will spend working on jobs. Then, we multiply that by “Efficiency” to determine how many billable hours will be produced in that amount of time. i.e. Previously a store may have been open 24, 8 hour days a month with 6 technicians for a total of 1008 clock hours. We multiplied 1008 by 90% Proficiency and it equaled 907 billable hours. How do you improve it? Are the techs the issue or the organization? Now you will be able to apply the “Efficiency” metric as well as the “Productivity” metric and see how each individually impacts your bottom line. i.e. 1008 clock hours times 85% Productivity = 857 hours on jobs times 106% technician “Efficiency” = 907 billable hours. Next: Controllable #5 - Effective Labor Rate. |

Ed AlosiThoughtful observer of actions and results in the Retail environment. Archives

February 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed